Rhythms of Regeneration: The Power of Dynamic Forces

A Dogma to Explore and Reconsider: A Scientific Look at the Literature at how Light Cyclic Intermittent Forces and Multi-Modal Resonance Outperform Static Loads in Stem Cell Differentiation

The field of regenerative medicine has undergone a paradigm shift, moving from a view of cell development dictated solely by biochemistry to one that integrates mechanobiology—the study of how physical forces regulate biological processes. While early tissue engineering often utilized static scaffolding to provide structural support, contemporary literature confirms that light, cyclic, and intermittent forces are far superior to static loads in driving stem cell differentiation.

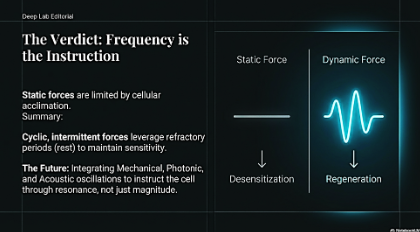

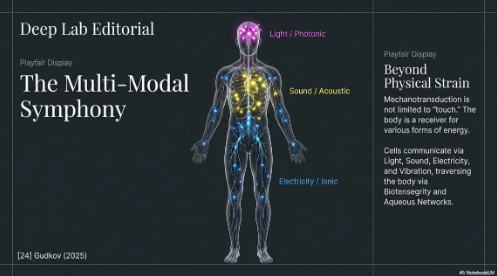

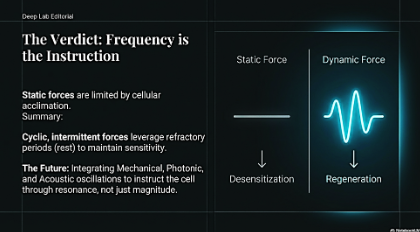

Static forces often lead to cellular "desensitization," whereas dynamic rhythms that include rest intervals mimic nature and our physiological environments (e.g., locomotion, heartbeats, breathing, respiration), maintaining cellular sensitivity and promoting ideal cellular development and proliferation. Furthermore, emerging research suggests that this "communication" extends beyond physical strain to include light, sound, electricity, and resonance within the body's fascial and aqueous networks via mechanotransduction and biotensegrity.

- The Limitation of Static Forces: Desensitization and Acclimation

A fundamental limitation of static mechanical loading is the phenomenon of cellular accommodation. 3 Bone cells and mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) rapidly acclimate to a constant stimulus, rendering prolonged static loading that are anabolic-ally inefficient.4

Research indicates that mechanosensitivity declines shortly after a stimulus is initiated. For example, in bone physiology, continuous cyclic loads without rest or static loads fail to sustain the osteogenic response. The cells effectively become used to or acclimated to the signal. This accommodation is linked to the saturation of signaling pathways, such as the polymerization of actin stress fibers and the downregulation of mechanosensitive receptors like P2Y2.5 Consequently, while static tension may provide initial cues for alignment, it is often insufficient for long-term tissue maturation and development.

- The Superiority of Cyclic and Intermittent Forces

Mechanotransduction plays a central role in the physiology of many tissues. Dynamic cyclic loading is associated with fluid movement around osteocytes, impacting cells multiple times per session compared to the single impact of a static force.5 The difference in force frequency leads to drastic differences in cellular response. Think osteoclastic (bone breakdown) versus osteoblastic (bone growth) differentiation.

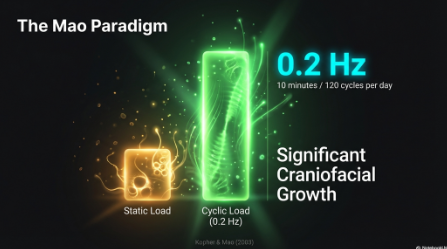

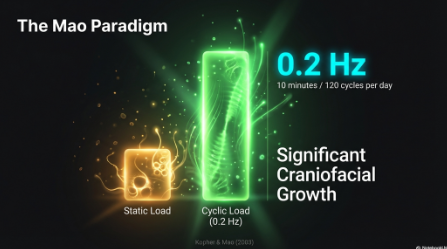

The Mao Paradigm: Suture Growth and Oscillatory Strain

Pivotal research by J.J. Mao and colleagues highlighted the critical importance of the oscillatory component of mechanical force. Their work demonstrated that suture growth is modulated by the oscillatory component of micromechanical strain rather than just the magnitude of the load.6 Specifically, they found that cyclic forces delivered at 0.2 Hz for just 10 minutes per day (120 cycles) evoked significantly more craniofacial growth and osteogenesis in the premaxillary suture than static forces of matching peak magnitude and duration.7 Further studies confirmed that both intramembranous bone and sutures respond robustly to in vivo cyclic tensile and compressive loading, reinforcing that the dynamic rhythm of the force is a primary driver of tissue regeneration.8

The "Rest Period" and Resensitization

The inclusion of rest intervals is a critical factor in optimizing differentiation. Research demonstrates that dividing a daily mechanical stimulus into discrete bouts separated by recovery periods significantly improves the osteogenic response.

- Restoration of Sensitivity: It takes approximately 4 to 8 hours for bone cells to fully recover mechanosensitivity after a loading bout.9

- Molecular "Second Spikes": Transcriptomic analysis reveals that inserting rest intervals allows for a recurring "second spike" in ERK1/2 phosphorylation, a key signaling molecule for differentiation.10 Continuous loading triggers only a single, transient spike, whereas intermittent loading sustains high levels of MAPK signaling necessary for osteogenesis. In engineered ligaments, intermittent cyclic stretch (e.g., 10 minutes of activity followed by 6 hours of rest) drives hierarchical collagen fiber maturation more effectively than continuous or static stretching.11,12 Transcriptomics is the comprehensive study of the transcriptome—the complete set of RNA transcripts (mRNA, non-coding RNA) produced by the genome—to analyze gene expression, regulation, and cellular processes.

- Fluid Shear Stress and Locomotion Frequencies

A critical mechanism by which dynamic forces drive differentiation is fluid shear stress. Unlike static compression, cyclic loading induces the movement of interstitial fluid through the extracellular matrix, exerting shear stress on cell membranes.

- Shear Stress vs. Static Load: Yourek, Mao, and Reilly (2010) demonstrated that shear stress independently induces the osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells.13 Their findings indicate that the dynamic fluid flow generated by cyclic loading is a more potent inducer of osteogenic genes (RUNX2, OSP, OPN) than static conditions, even in the absence of osteogenic supplements.

- The Locomotion Frequency (2 Hz): A systematic study on cyclic hydrostatic pressure identified 2 Hz as the optimal frequency for inducing osteogenic development in human bone marrow stem cells.14 This frequency mimics the stride rate of human locomotion, effectively driving early osteogenic gene expression (COX2) and late-stage mineralization by replicating the physiological pumping of marrow fluid.

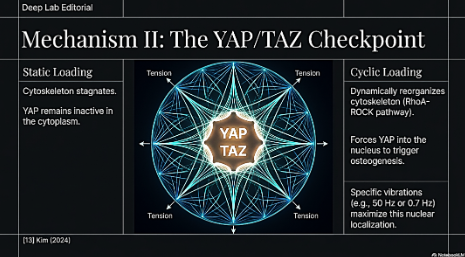

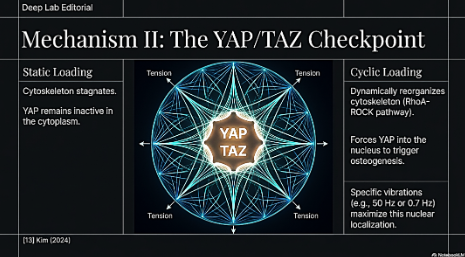

- Molecular Mechanisms: The YAP/TAZ Checkpoint

The transduction of these dynamic forces relies on the Hippo pathway effectors YAP (Yes-associated protein) and TAZ. Cyclic stretching promotes the nuclear localization of YAP, which is essential for osteogenesis.

- Dynamic Remodeling: This process is regulated by the RhoA-ROCK pathway and cytoskeletal tension as in biotensegrity.15 Unlike static loading, cyclic loading dynamically reorganizes the cytoskeleton and its compressive and tension elements, maintaining the nuclear YAP activity required for differentiation.

- Frequency Dependence: The response is highly frequency dependent. For example, specific vibrational frequencies (e.g., 50 Hz)16 or tensile strain frequencies (e.g., 0.7 Hz) 17 have been shown to maximize osteoblastic differentiation markers like Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP).

- Multi-Modal Communication: Light, Sound, Electricity, and Fascia

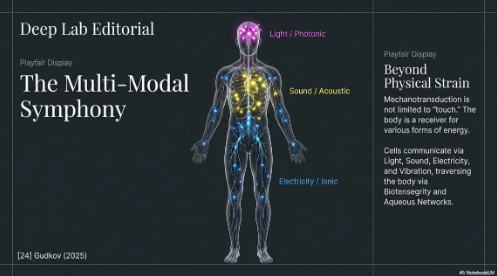

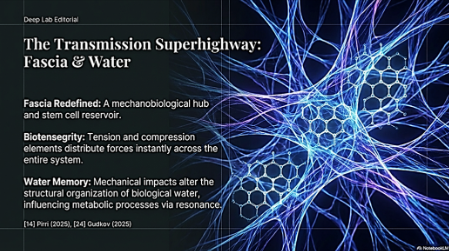

Dentists utilize and communicate via orthodontic forces and laser light energy daily. Understanding this communication better will serve our patients better and give us a better understanding of how it can affect our lives too. This communication (mechanotransduction) of signals (energy, sound, electromagnetism, light, vibrations, frequencies, wavelengths) throughout the body via resonance, water, fascia, and meridian pathways are dictated by their own unique coherence and biotensegrity parts.

Current literature supports the integration of these multi-modal signals in regenerative medicine:

- Light and Laser Energy (Photobiomodulation): High-Intensity Laser Therapy (HILT) and photobiomodulation (PBM) act as potent biophysical signals. Studies indicate that PBM combined with mechanical vibration (HFMV) significantly improves bone quality (trabecular number) and reduces inflammatory markers (COX-2, RANKL) during orthodontic retention.18 This suggests that light energy can modulate the inflammatory-regenerative balance, synergizing with mechanical forces to stabilize tissue.

- Sound and Acoustic Resonance: Acoustic-frequency vibratory stimulation (AFVS) demonstrates that sound waves can regulate stem cell differentiation.19,20 Stimulation of gingival-derived MSCs at 60 Hz significantly enhanced osteogenic markers like Collagen Type I and Osteopontin compared to static controls. Mechanisms such as "oscillatory coherence" suggest that specific sound frequencies vibrate cell nuclei and cytoskeletal elements, triggering biochemical responses like physical strain.21

- Electromagnetism and Electricity: Stem cells are electrically sensitive. Co-stimulation using cyclic strain and electrical fields has been shown to produce a synergistic effect, promoting neural differentiation of MSCs better than either stimulus alone. 22 Furthermore, electrical stimulation can increase intracellular calcium influx, activating the calcineurin/NFAT pathway to drive osteogenesis, mirroring the calcium oscillations triggered by cyclic fluid flow.23

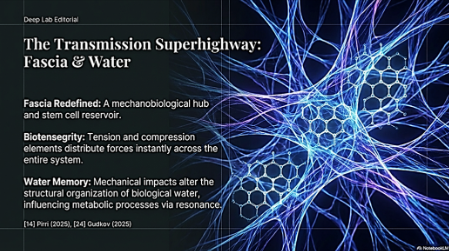

- Fascia, Water, and Biotensegrity: These signals are transmitted through the body's continuous fibrous network. Fascia is now redefined as a mechanobiological hub and stem cell reservoir, capable of transmitting tension to its compressive elements and directing regeneration across the body.2 This transmission relies on Biotensegrity, the architectural principle where tension and compression elements (cytoskeleton, ECM) distribute forces instantly across the system. Furthermore, mechanical impacts on Aqueous Solutions within biological systems can alter the structural organization of water, influencing metabolic processes and gene expression (e.g., Osx, RANKL) through resonance and frequency-dependent effects.24

Conclusion

The literature strongly supports the conclusion that light, cyclic, and intermittent forces constitute the optimal mechanical environment for stem cell differentiation. Static forces are limited by the inevitable desensitization of cellular receptors. In contrast, cyclic intermittent regimes leverage the cell's refractory periods to maintain mechanosensitivity, induce recurring signaling spikes, and drive robust cytoskeletal reorganization. As evidenced by the work of Mao, Robling, and others, the frequency, resonance, and oscillatory nature of the signal—whether mechanical, photonic, or acoustic—are often more instructive to the cell than the sheer magnitude of the force.

References

- The Diminishing Returns of Mechanical Loading and Potential Mechanisms that Desensitize Osteocytes. Gardinier JD. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2021;19(4):436–443. doi: 10.1007/s11914-021-00693-9.

- Mechanical Signaling for Bone Modeling and Remodeling. Robling AG, Turner CH. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2009;19(4):319–338. doi: 10.1615/critreveukargeneexpr.v19.i4.50.

- Static and Cyclic Mechanical Loading of Mesenchymal Stem Cells on Elastomeric, Electrospun Polyurethane Meshes. Cardwell RD, Kluge JA, Thayer PS, Guelcher SA, Dahlgren LA, Kaplan DL, Goldstein AS. J Biomech Eng. 2015;137(7):0710101. doi: 10.1115/1.4030404.

- Recovery periods restore mechanosensitivity to dynamically loaded bone. Robling AG, Burr DB, Turner CH. J Exp Biol. 2001;204(Pt 19):3389–99. doi: 10.1242/jeb.204.19.3389.

- Systems-Based Identification of Temporal Processing Pathways during Bone Cell Mechanotransduction. Worton LE, Ausk BJ, Downey LM, Bain SD, Gardiner EM, Gross TS, Kwon RY. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(9):e74205. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074205.

- Suture Growth modulated by the oscillatory component of micromechanical strain. Kopher RA, Mao JJ. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18(3):521–528. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.3.521.

- Strain induced osteogenesis of the craniofacial suture upon controlled delivery of low-frequency cyclic forces. Mao JJ, Wang X, Kopher RA. Front Biosci. 2003;8:a10–17. doi: 10.2741/1011.

- Responses of intramembranous bone and sutures upon in vivo cyclic tensile and compressive loading. Peptan AI, Lopez A, Kopher RA, Mao JJ. Bone. 2008;42(2):432–438. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.10.010.

- Mechanical forces direct stem cell behaviour in development and regeneration. Vining KH, Mooney DJ. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2017;18(12):728–742. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2017.108.

- Optimizing an Intermittent Stretch Paradigm Using ERK1/2 Phosphorylation Results in Increased Collagen Synthesis in Engineered Ligaments. Paxton JZ, Hagerty P, Andrick JJ, Baar K. Tissue Eng Part A. 2012;18(3-4):277–284. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2011.0336.

- Intermittent Cyclic Stretch of Engineered Ligaments Drives Hierarchical Collagen Fiber Maturation in a Dose- and Organizational-Dependent Manner. Troop LD, Puetzer JL. Acta Biomater. 2024;185:296–311. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2024.07.025.

- Shear stress induces osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. Yourek G, McCormick SM, Mao JJ, Reilly GC. Regen Med. 2010;5(5):713-724. doi: 10.2217/rme.10.60.

- YAP mechanotransduction under cyclic mechanical stretch loading for mesenchymal stem cell osteogenesis is regulated by ROCK. Kim E, Riehl BD, Bouzid T, Yang R, Duan B, Donahue HJ, Lim JY. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2024;11:1306002. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2023.1306002.

- Redefining Fascia: A Mechanobiological Hub and Stem Cell Reservoir in Regeneration—A Systematic Review. Pirri C, Pirri N, Petrelli L, De Caro R, Stecco C. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26(20):10166. doi: 10.3390/ijms262010166.

- Physiological cyclic hydrostatic pressure induces osteogenic lineage commitment of human bone marrow stem cells: a systematic study. Stavenschi E, Corrigan MA, Johnson GP, Riffault M, Hoey DA. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2018;9:276. doi: 10.1186/s13287-018-1025-8.

- Enhancement of Osteogenic Differentiation and Proliferation in Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells by a Modified Low Intensity Ultrasound Stimulation under Simulated Microgravity. Uddin SMZ, Qin Y-X. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e73914. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073914.

- Effects of mechanical vibration on proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of human periodontal ligament stem cells. Zhang C, Li J, Zhang L, Zhou Y, Hou W, Quan H, Li X, Yu H. Arch Oral Biol. 2012;57(10):1395–1407. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2012.04.010.

- Effect of Tensile Frequency on the Osteogenic Differentiation of Periodontal Ligament Stem Cells. Wang W, Wang M, Guo X, Zhao Y, Ahmed MMS, Qi H, Chen X. Int J Gen Med. 2022;15:5957–5971. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S368394.

- Possible Mechanisms for the Effects of Sound Vibration on Human Health. Bartel L, Mosabbir A. Healthcare (Basel). 2021;9(5):597. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9050597.

- Three-dimensional imaging and molecular analysis of the effects of photobiomodulation and mechanical vibration on orthodontic retention treatment in rats. Öztürk T, Amuk NG. Lasers Med Sci. 2022;37:3517–3526. doi: 10.1007/s10103-022-03632-8.

- Vibration-assisted orthodontic treatment: A study of acoustic-frequency vibratory stimulation on gingival tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Ríos-García CA, García-Lee V, Fajardo G, González-Alva P. Preprint. 2025.

- Cyclic Strain and Electrical Co-stimulation Improve Neural Differentiation of Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Cheng H, Huang Y, Chen W, Che J, Liu T, Na J, Wang R, Fan Y. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:624755. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.624755.

- Effect of direct current electrical stimulation on osteogenic differentiation and calcium influx. Moon H, Lee M, Kwon S. Biomed Eng Lett. 2023;13:171–180. doi: 10.1007/s13534-023-00267-3.

- Diversity of Effects of Mechanical Influences on Living Systems and Aqueous Solutions. Gudkov SV, Pustovoy VI, Sarimov R, Shcherbakov IA. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26:5568.